Theatre on the Small Screen: The Movement of Theatre onto Digital Platforms.

Traditionally, from the time of Wagner, theatre has almost invariably been performed within a dedicated, ritualistic building on a pre-prepared stage. The variables of that stage have been controlled by the performing company: lighting, temperature, design, space allowance, and audience position are all handled within the building environs. These variables have been utilised as a method of directing and engaging the attention of each spectator to create ‘the audience’, a single entity to balance ‘the cast’. “[Wagner’s] intent was to maximise the suspension of belief, to draw the viewer into an illusionary world staged within the proscenium arch” (Packer & Jordan, 2001, p.xxiv). The modern consumer desire for the staging of theatrical productions on pocket-sized monitors, made possible through multimedia developments and the drive of digital cultures in recent years, removes viewers from this stage-front viewpoint, thereby affecting immersion and liveness. This essay will use examples to examine some of the theoretical background of theatre development within the digital age, so analysing the advancement of the theatre stage from a physical entity to small screen digital platforms such as YouTube accessed through PCs, mobile phones, and tablets. Text tools in the form of Google Ngram will be used to try and assess the rapidity with which digital cultures are affecting traditional views of the theatre.

Whilst there are those who believe in digital cultures as an avenue of artistic progression, many theorists are instead concerned with the negative impact of both the mechanical and the digital on artistic creation. These concerns were outlined in the work of Walter Benjamin (1936), who focused on the perceived ‘aura’ of the original art piece, proselytising its ‘liveness’ could only be absorbed through engagement with that piece in its ritualistic space, “its unique existence in the place where it is at this moment” (Benjamin, 1936, p12). A mechanical reproduction could therefore not replace access to the original piece, but only provide a pale reflection. Considering a theatre performance as a singular artistic creation both fixed in time and space, and inherently connected to literature and narrative, each production that is remediated or mediatised has the additional problem of ensuring the viewers understanding of the playwright’s original intent. In effect, “communication is intersubjective” (Ong, 1988, p173): there is a basic requirement for language to be seen as well as heard.

The advent of digital cultures as a performance platform offers widened participation by those who would not usually engage with the theatre, but also removes the staging control traditional within a performed piece. Full productions are rare on digital platforms, at least partly due to their economic constraints, with popular desire for this kind of entertainment potentially being met by YouTube shorts rather than theatre attendance. YouTube stars and classically trained actors are two very different groups, with internet stars often starting as young people with no formal training and a background in either gaming or comedy skits performed to live or media audiences as a hobby (Taylor, 2017). While there are theatre companies working on the movement of the classical stage concept into new media, so far this has mostly taken the form of digital advertising for forthcoming productions, such as the 2012 case of Headlong Theatre, which controversially produced a filmic commercial for their forthcoming theatre season and released it on YouTube and Twitter (Unitt, 2012). The pushing out of a staged performance through technological means remediates the piece, and according to Benjamin (1936), effectively loses its original artistic aura, and therefore its liveness.

The strive for liveness whilst remediating performed art can be summarised by the somewhat opposing works of Peggy Phelan and Phillip Auslander. Whilst the works of both begin with Benjamin, Phelan is the more Benjamin-core centric of the two, and her arguments stem particularly from the perceived need for art to be seen and for consumers of art to be seen in the ritualistic location in which the art is located (the ‘reciprocal gaze’). “While the notion of the potential reciprocal gaze has been considered part of the ‘unique’ province of live performance, the desire to be seen is also activated by looking at inanimate art” (Phelan, 1996, p4). From this point, Phelan’s natural progression is to recognise that something is going to be lost should the performance not be viewed so. “Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so it becomes something other than performance” (Phelan, 1996, p146). For Phelan, the disappearance of performance into the memory of the audience is its strength, “into the realm of invisibility and the unconscious where it eludes regulation and control” (Westerman, 2015).

Auslander in contrast works from evidence supporting Benjamin’s statement that a “reproduced work of art is to an ever-increasing extent the reproduction of a work of art designed for reproducibility” (Benjamin, 1936, p19), and further argues that performance has already been irretrievably mediatised by the incursion of televised principles, therefore suggesting that “thinking about the relationship between live and mediatised forms in terms of ontological oppositions is not especially productive, because there are few grounds on which to make significant ontological distinctions” (Auslander, 2008, p55). Perhaps more realistically than Phelan, Auslander acknowledges that reproducibility of artworks is a given in a digital age, and instead seeks a stable basis on which theatre production can survive within a digital framework.

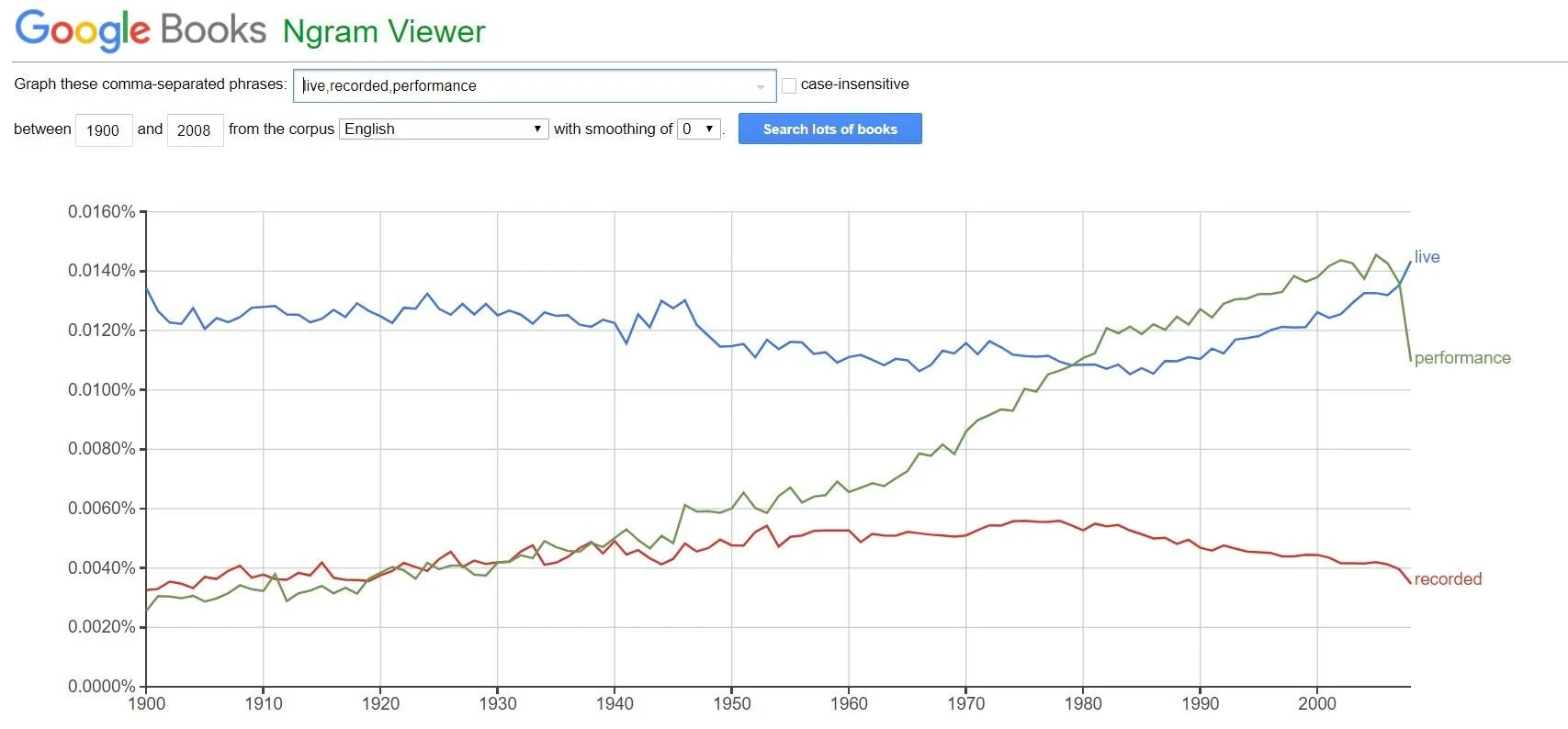

In an attempt to analyse the rapidity with which theatre performance is becoming pressured by digital advancement, the following Google Ngram text tool analysis has been utilised. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the words live, recorded, and performance in a broad bank of literature. The slight but continuous increases in the use of the words ‘recorded’ and ‘performance’ initiating in the 1920s probably reflect the uptake of “the wireless” in homes from around 1924 (Wikipedia, 2017a), and the resulting initiation of mediatisation. “Throughout history, performance has employed available technologies and has been mediated in one sense or another. It is only since the advent of mechanical and electric technologies of recording and reproduction however that performance has been mediatised” (Auslander, 2008, p58).

In terms of the more recent changes shown in Figure 1, and in accordance with both Aulander’s arguments and the way that literature often reflects cultural and social developments, it was expected that, despite the multiple linguistic meanings and uses of the words themselves, there would be a reduction in the use of the word live and a simultaneous increase in the words recorded and performance, when Figure 1 apparently shows the opposite to be the case, with results most pronounced for the word performance. It is possible that the increasing academic and media attention being drawn to the plight of modern theatre has skewed the results slightly, which are further limited by Google Ngram only being operational until 2008 inclusively, but these findings may instead support Auslander’s suspicion that the loss of liveness stems in part from the economic impact on Broadway of productions beginning as an art-piece “designed for reproducibility” (Benjamin, 1936, p19), rather than being a true live performance. “I noticed that a number of the Broadway productions I was seeing had been underwritten in part by cable television money on the understanding that taped versions of the productions would appear later on cable networks…the productions themselves (particularly their sets, but also their staging) were clearly ‘camera-ready’ – preadjusted to the aspect ratio, intimate scale, and relative lack of detail of the television image” (Auslander, 2008, p30). There is certainly an approximate change from around 1980 in the use of these words in popular literature.

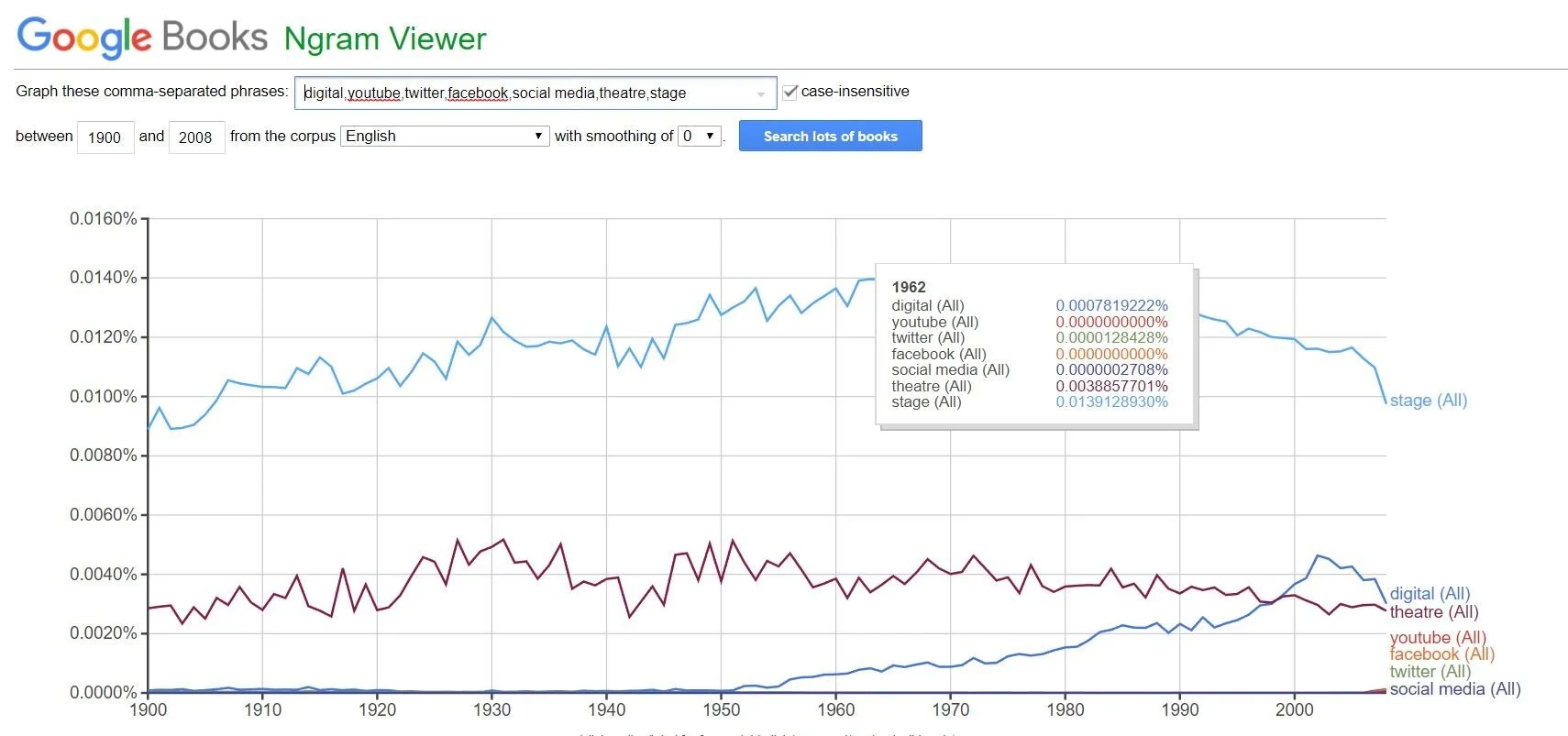

Figure 2 begins by analysing the proliferation of the words digital, stage, and theatre against the words YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and social media from 1900 to 2008. The sharp upturn of previously unused words relating to social media can be seen, as can an odd recent decline in the word digital. This could possibly be explained by digital becoming commonplace, and therefore not needing referencing in modern literature. The upswing in new terms is mirrored by a sharp and recent decline particularly in the word stage.

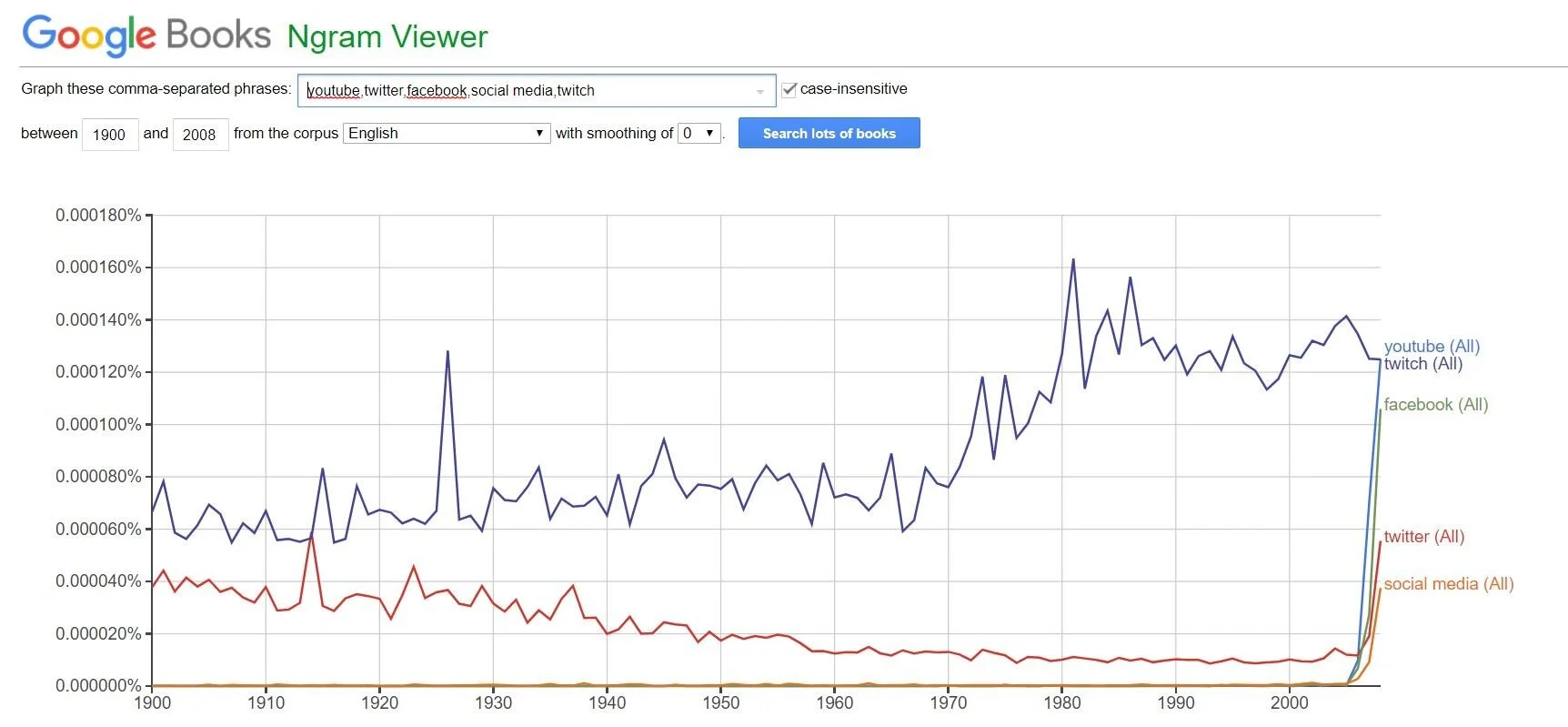

Figure 3 shows a similar analysis to that in Figure 2, with the stage and theatre detail stripped away so that the sharp increase in social media related terms can more easily be seen. It was expected that the words Twitch and Twitter would show no change, as these are established words that became names of digital platforms, but surprisingly Twitter has experienced the same sharp increase as the rest and the word Twitch flatlines into steady regular usage in line with the release of the live stream option the platform is based on in 2006 (Wikipedia 2017c).

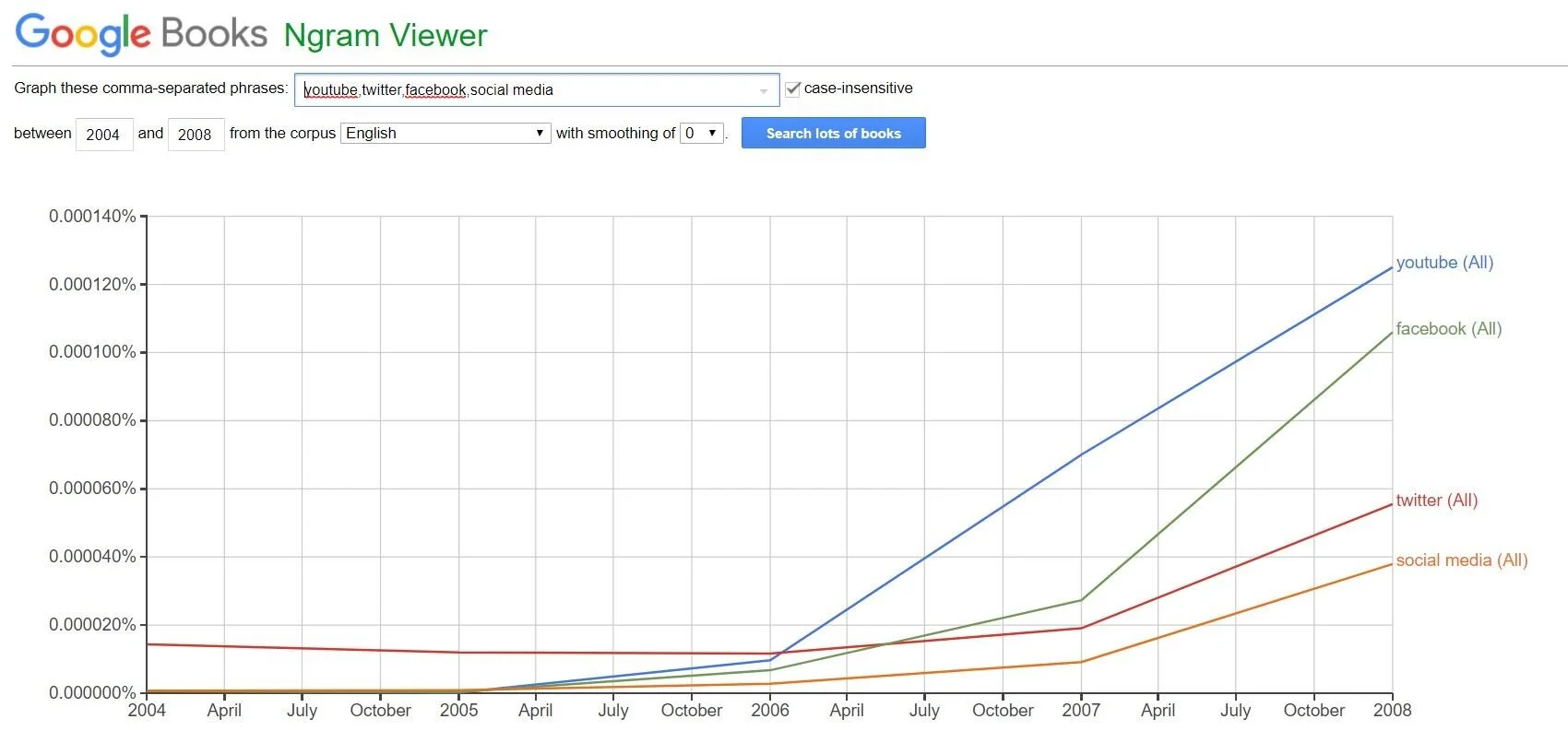

Finally Figure 4 shows a detailed view of the proliferation of social media related words in general literature by limiting the search period to 2004 to 2008. This clearly shows the atmospheric rise of YouTube as a medium, and supports the supposition that YouTube is the chosen interface for a significant audience engaging with a certain style of staged performance.

Whilst both Phelan and Auslander have valid points and real concerns regarding the impact of the digital on theatre, the progression of a specific style of staged performance onto the small screen, which could be referred to as YouTube Theatre, means that Auslander’s mediatisation is now creeping into the realm of virtual reality. The YouTube-style performances that people are engaging with through computer screens, smart phones, and tablets are enabled for augmented reality combinations of live performance with recorded, animated, and written overlays and additions; something that live performance is attempting to keep pace with by utilising digital tools. “Live performance now often incorporates mediatisation to the degree that the live event itself is a product of media technologies” (Auslander, 2008, p25). Virtual reality is really nothing new within staged performance; the concepts involved have been part of the performing arts since their inception. A variety of means have been used to transport the audience into the world created on the stage, thereby entwining the concepts of virtual reality and immersion. By 2001, as virtual reality promises began to emerge within digital cultures, it was already anticipated that computer-based multimedia would make encounters with immersive, virtual worlds commonplace. “Virtual reality, after all, is a logical extension of the integration of the arts” (Packer & Jordan, 2001, p.xxii).

Whilst the adaptation of performance to suit a modern audience seems positive, the unfortunate reality is that engagement is still with the digital platform, not with live theatre. Liveness by Auslander shows a decline in the percentage of the population accessing live theatre and dance performances, but an increase in percentages accessing televised performance; the obvious but impossible response to this is to roll live theatre directly out onto digital platforms. The major issues for live performance are cost combined with accessibility; a significant proportion of the population will neither pay or attend. Traditionally there has been one major contender for popular theatre; Peter Brook (1968) defined this as Rough Theatre: “it is always the popular theatre that saves the day”. Brook described rough theatre as “salt, sweat, noise, smell: the theatre that’s not in a theatre, the theatre on carts, on wagons, on trestles, audiences standing, drinking, sitting round tables, audiences joining in, answering back…”; stand-up comedy and pantomime both fall into this description, as do many events that have been considered as much performance art as theatre, and, setting aside for the moment the traditional concept of the theatre stage, it is this type of production that is becoming most prevalent on social media platforms, and that are most watched on small screens.

Taylor, 2017 describes recent examples of a combination of performance art and comedy, particularly from the metamodernist actor Shia LaBeouf, that have used the small screen to great effect to mediatise, rather than remediate, the original piece performed. Modern performances are commonly remediated; as Auslander states, they are performed with the expectation of recording, and are therefore remediated before they are even performed; this has been considered a loss of value by such theorists as Phelan. Some of the recent performances enacted by artists such as LaBeouf have taken the concepts of virtual reality and mediatisation and arguably created something new; the initial performance is generated, often to a small surprised audience, whose mediatisation of the original act effectively becomes the performance “viewers have increasingly become constructed as self-aware participants” (Nelson, p137). This potentially overturns the resistance to reproduction and instead makes the reproduction the aim; if Phelan is concerned that the value of performance is to move its way into the consciousness of the audience, then many of LaBeouf’s performances achieve this, whilst simultaneously and continually adapting to societal draws and reaching and interacting with a larger audience than a single performance on stage ever has. In the words of Giannachi (2004, p123) “virtual reality offers fluid and open forms that allow for the viewer simultaneously to be inside and outside the work of art. The viewer is therefore always dispersed, and the work of art takes place through the dispersion and displacement thus caused”.

Whilst any method of engagement seems positive for the future of theatre, the reality is that LaBeouf is both a seasoned live comic and Hollywood actor, and a minority example, who could in reality have no aim in mind and simply be playing a social media popularity game. While there are some great performers on YouTube, there was a marked failure in their ability to perform live in the YouTube 2013 Live Comedy Week; experienced live performers took the positive reviews (Gutelle, 2013). It is conversely true that despite the example of LaBeouf, in an economic climate where theatre companies need to draw a significant income from their performances, they continue to have serious problems in finding ways to incorporate the small screen into theatrical performance that positively accommodate and engage the audience. As in the example of Headlong Theatre, this has taken the form of televised YouTube trailers, internet-based development material for developing playwrights as with the Royal Court Theatre Playwriting Toolkit, and YouTube theatre channels, where such as the National Theatre stream trailers, interviews, and audience feedback. Most of the expected audience participation is for them to receive a sales enticement; in an age where there are excellent free memes and short productions that are disputably equivalent to short, sharp theatre skits, directly accessible on a smartphone, this is not a popular method of audience attraction. As of July 2017, the National Theatre channel has 23,044 subscribers. Despite not having a dedicated channel, LaBeouf’s single most popular video had been viewed 49 million times. “Live forms have become mediatised…they have been forced by economic reality to acknowledge their status as media within a mediatic system that includes the mass media and information technologies” (Auslander, 2008, p5). The evidence suggests a clear need for the blending of experienced live performers with the energy, rapidity and liveliness of the digital small screen for the future of theatre performance: “while the human is tending towards a cyborgian, post-human existence, the computer is becoming increasingly human” (Giannachi, 2004, p134).

REFERENCES

Auslander, P. (2008) Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (Second Edition). London: Routledge.

Benjamin, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London: Penguin.

Brook, P. (1968) The Empty Space. New York: Touchstone.

Giannachi, G. (2004) Virtual Theatres: An Introduction.

Gutelle, S. (2013) Six reasons why YouTube’s ‘big live comedy show’ didn’t work. Los Angeles: Tubefilter [Online]. Available from: http://www.tubefilter.com/2013/05/20/youtube-big-live-comedy-show-fail/ [Accessed 25 June 2017].

Nelson, R. (2017) New Small Screen Spaces: A Performative Phenomenon. In: Chapple & Kattenbelt (eds.). Intermediality in Theatre and Performance. New York: Rodopi.

Ong, W. (1988) Orality & Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge.

Packer, R. & Jordan, K. (2001) Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality. New York: Norton & Company Inc.

Phelan, P. (1996) Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. New York: Routledge.

Taylor, S. (2017) YouTube Theatre: An Academic Poster Presentation. Sheffield: PostImage [Online]. Available from: https://s25.postimg.org/keeyjj1hr/You_Tube_Theatre_Jun17.png [Accessed 24 July 2017].

Unitt, C. (2012) Falling Headlong: A theatre trailer case study. UK: Chris Unitt Blog [Online]. Available from: http://www.chrisunitt.co.uk/2012/04/falling-headlong-a-theatre-trailer-case-study/ [Accessed 26 July 2017].

Westerman, J. (2015) Between Action and Image: Performance as ‘Inframedium’. Britain: TATE [Online]. Available from: http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/between-action-and-image-performance [Accessed 26 July 2017].

Wikipedia (2017a) History of Radio. California: Wikipedia [Online]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_radio [Accessed 26 July 2017].

Wikipedia (2017b) Myron W. Krueger. California: Wikipedia [Online]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myron_W._Krueger [Accessed 26 July 2017].

Wikipedia (2017c) Twitch.tv. California: Wikipedia [Online]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twitch.tv [Accessed 06 May 2017].

Harvard reference if accessing item for use:

Taylor, S. (2017). Theatre on the Small Screen. Sheffield: Squarespace. [Online]. Available from: www/fairfaxcuratorart/gaming-narratives-portfolio/small-screen-theatre [Accessed Date].